JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP via Getty Images

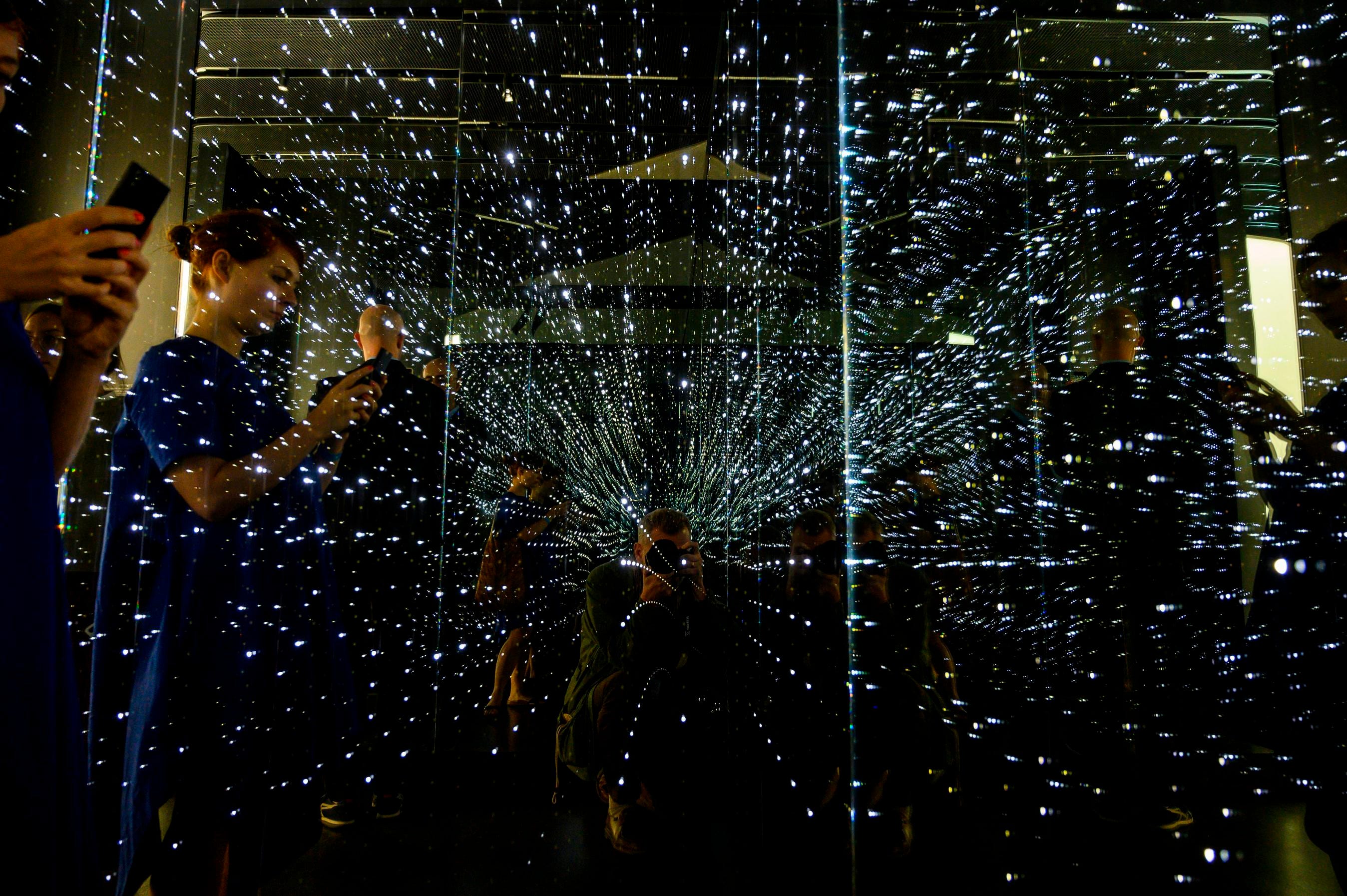

This is the moment of the year for reflections—and how to apply learnings going forward. Doing this exercise with a focus on artificial intelligence (AI) and data might have never been more important. The release of ChatGPT has opened a perspective on the future that is as mesmerizing—we can interact with a seemingly intelligent AI that summarizes complex texts, spits out strategies, and writes somewhat solid arguments—as it is frightening (“the end of truth”).

What moral and practical compass should guide humanity going forward in dealing with data-based technology? To answer that question, it pays off to look to nonprofit innovators—entrepreneurs focused on solving deeply entrenched societal problems. Why they can be of help? First, they are masters for spotting the unintended consequences of technology early, and figure out how to mitigate them. Second, they innovate with tech and build new markets, guided by ethical considerations. Here, then, are five principles, distilled from looking at the work of over 100 carefully selected social entrepreneurs from around the world, that shed light on how to build a better way forward:

Artificial intelligence must be paired with human intelligence

AI is not wise enough to interpret our complex, diverse world—it’s just bad at understanding context. This is why Hadi Al Khatib, founder of Mnemonic, has built up an international network of humans to mitigate what tech gets wrong. They rescue eyewitness accounts of potential war crimes—now mostly Ukraine, earlier Syria, Sudan, Yemen—from being deleted by YouTube and Facebook. The platforms’ algorithms neither understand the local language nor the political and historic circumstances in which these videos and photos were taken. Mnemonic’s network safely archives digital content, verifies it—yes, including with the help of AI—and makes it available to prosecutors, investigators, and historians. They provided key evidence that led to successful prosecution of crimes. What is the lesson here? The seemingly better AI gets, the more dangerous it gets to blindly trust it. Which leads to the next point:

AI cannot be left to technologists

Social scientists, philosophers, changemakers and others must join the table. Why? Because data and cognitive models that train algorithms tend to be biased—and computer engineers will in all likelihood not be aware of the bias. More and more research has unearthed that from health care to banking to criminal justice, algorithms have systematically discriminated—in the U.S., predominantly against Black people. Biased data input means biased decisions—or, as the saying goes: garbage in, garbage out. Gemma Galdon, founder of Eticas, works with companies and local governments on algorithmic audits, to prevent just this. Black Lives Matter, founded by Yeshi Milner, weaves alliances between organizers, activists, and mathematicians to collect data from communities underrepresented in most data sets. The organization was a key force in shedding light on the fact that the death rate from Covid-19 was disproportionately high in Black communities. The lesson: In a world where technology has an outsized impact on humanity, technologists need to be helped by humanists, and communities with lived experience of the issue at hand, to prevent machines getting trained with the wrong models and inputs. Which leads to the next point:

It’s about people, not the product

Technology must be conceptualized beyond the product itself. How communities use data, or rather: how they are empowered to use it, is of key importance for impact and outcome, and determines whether a technology leads to more bad or good in the world. A good illustration is the social networking and knowledge exchange application SIKU (named after the Inuktitut word for sea ice) developed by the Arctic Eider Society in the North of Canada, founded by Joel Heath. It allows Inuit and Cree hunters across a vast geographic area to leverage their unique knowledge of the Arctic to collaborate and conduct research on their own terms—leveraging their language and knowledge systems and retaining intellectual property rights. From mapping changing sea-ice conditions to wildlife migration patterns, SIKU lets Inuit produce vital data that informs their land stewardship and puts them on the radar as valuable, too often overlooked experts in environmental science. The key point here: It is not just the app. It’s the ecosystem. It’s the app co-developed with and in the hands of the community that produce results that maximize community value. It’s the impact of tech on communities that matters.

MORE FOR YOU

Profits must be shared fairly

In a world that is increasingly data driven, allowing a few big platforms to own, mine, and monetize data, all is dangerous—not just from an anti-trust perspective. The feared collapse of Twitter brought this to the collective conscience: journalists and writers who built up an audience for years suddenly risk losing their distribution networks. Social entrepreneurs have long started to experiment with different kinds of data collectives and ownership structures. In Indonesia, Regi Wahyu enables small rice farmers at the base of the income pyramid to collect their data—land size, cultivation, harvest—and put it on a blockchain, rewarding them each time their data is accessed, and allowing them to cut out middlemen for better profits. In the U.S., Sharon Terry has grown Genetic Alliance into a global, patient driven data pool for the research of genetic diseases. Patients keep ownership of their data and have stakes in a public benefit corporation that hosts it. Aggregate data gets shared with scientific and commercial researchers for a fee, and a share of the profits from what they find out gets passed back and redistributed to the pool. Such practices illustrate what Miguel Luengo called “the principle of solidarity in AI” in an article in Nature: the fairer share of gains derived from data, as opposed to the winner takes it all.

The negative externality costs of AI must be priced in

The aspect of solidarity leads to a larger point: the fact that currently, the externality costs of algorithms are borne by society. The prime case in point: social media platforms. Thanks to the way recommendation algorithms work, outrageous, polarizing content and disinformation spread faster than considerate, thoughtful posts, leading to a corrosive force that undermines trust in democratic values and institutions alike. At the core of the issue: surveillance capitalism, or the platform business model that incentivizes clicks over truth, engagement over humanity, and allows commercial as well as government actors to manipulate opinions and behavior at scale. What if that business model became so expensive that companies would have to change it? What if society pressed for compensation for the externality costs—polarization, disinformation, hatred? Social entrepreneurs have used strategic litigation, pushed for updated regulation and legal frameworks, and are exploring creative measures such as taxes and fines. The field of public health might provide clues. After all, taxation on cigarettes has been the cornerstone for reducing smoking and controlling tobacco.

The article was originally posted at: %xml_tags[post_author]% %author_name% Source%post_title%